Kung Fu Theatre: Beginner’s Guide to Watching Kung Fu Movies (Pt. 1)

Sometimes I invite friends unfamiliar with the kung fu genre to my Kung Fu Movie Night hoping to perhaps indoctrinate new fans. However, I often forget there are sometimes steep cultural and genre hurdles that can impede the enjoyment for a new recruit. This guide is designed to help the newcomer interested in watching kung fu movies manage their expectations as well as partially explain the origin behind a lot of these foreign tropes.This list focuses solely on Hong Kong-brand wuxia, as they are considered the gold standard of martial arts movies. No, Hollywood doesn’t even come CLOSE, as hopefully newcomers will soon discover. I’ve split this up into two parts to first cover the practical side of wuxia films, then we’ll talk about the cultural idiosyncrasies in part 2.

What is Wuxia?

Wuxia is a term that translates to “Martial Hero” or “Martial chivalry,” and is the name given to the kung fu movie genre, much like Westerns, Sci-Fi or Drama are considered genres. Martial chivalry could be compared to the Bushido code of feudal Japan or knighthood in medieval Europe. It doesn’t just imply martial arts expertise, but also encompasses practicing the unwritten laws of the martial hero. This usually involves a hero from simple means who needs to fight in the defense of an oppressed people, who of course is a master at martial arts.

I would say not all kung fu movies are considered wuxia, but it is a term that you’ll see used interchangeably across the genre regardless.

The Stunts Are Real

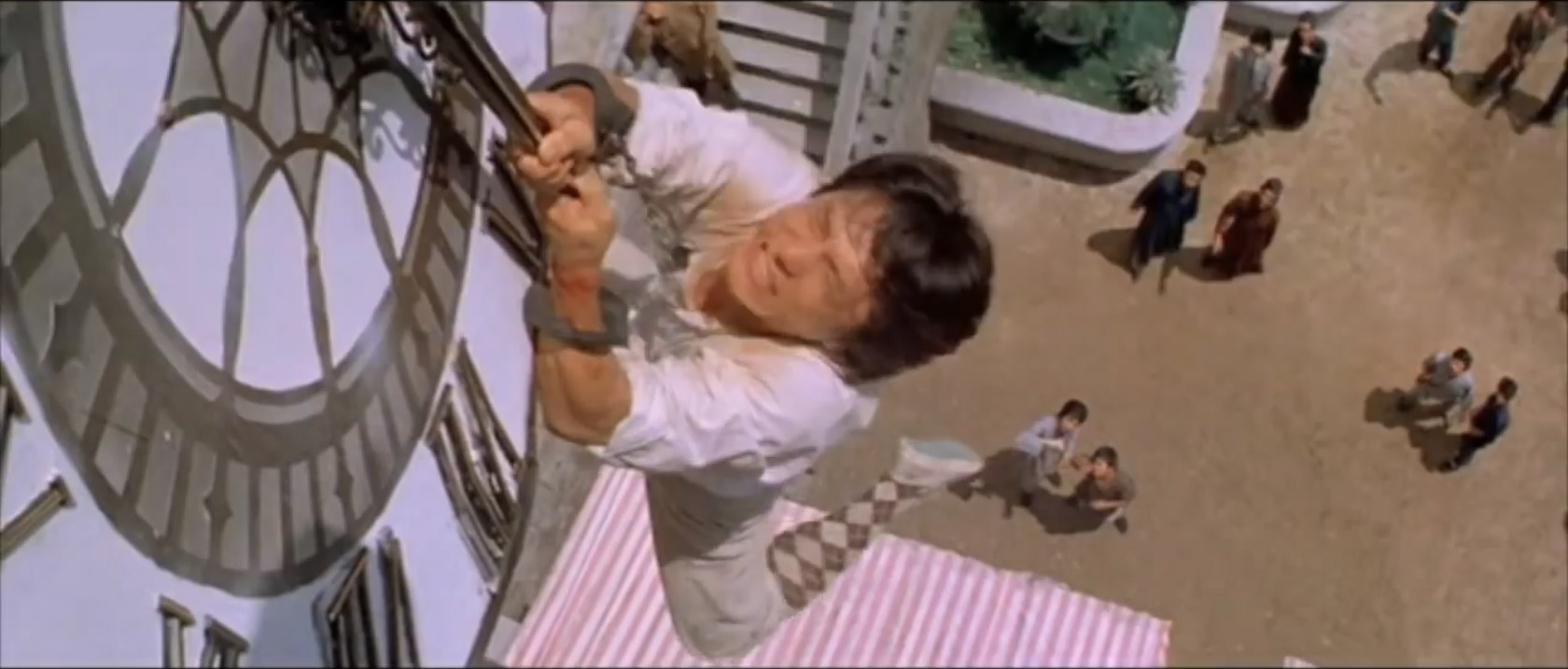

Jackie is literally hanging to dear life. No green screen, no nets. Just cold hard ground 40 feet below.

This is probably the craziest thing I try to instill upon newcomers. Hong Kong stuntmen are absolutely the craziest people on earth. While it pains me to see people risk life and limb over a simple movie, it’s the same reason why I love it. It’s that “Cabin in the Woods” mentality that keep drawing me and millions of other fans back for more.

I originally didn’t see the big deal when I was told Jackie Chan did all his own stunts. Several big stars in the West also do their own stunts. However, when you see HK stunts you realize how outrageous they are. They are almost always incredibly dangerous, and often there are almost always no safety wires or nets. This is typically because (as most things of this list) they have no budget to do it safely or with special effects.

Here’s Yuen Biao, one of the best in the biz, showing off his incredible acrobatics in Dragons Forever:

[youtube id=”khWcczhXgKQ” align=”center” mode=”lazyload” autoplay=”no”]

Make sure to watch carefully, because you will often see full shots where you watch a person fall 10-20 feet off a building onto the ground – no cutaways. I originally started watching these movies for the martial arts, but the stunts are now a key component of the fun as well.

The Action Is (Mostly) Real

A 5 minute fight can take weeks to shoot because of the complexity, importance and difficulty of creating it. The directors knew the reason people liked their movies was because of their elaborate fight scenes, so a majority of their energy and budget was often dedicated to them.

To further enhance the realism of their fight sequences, they often use what they call “gold dust.” The fighters cover themselves in dust that is easily picked up by the camera, that way when one of the actors is “hit,” you will see a puff of dust as a result of the impact. Though they will wear padded clothing and still pull their punches, people often get hurt… all for the glorious shot.

Here’s a prime example featuring two of the best: Donnie Yen vs. Sammo Hung from SPL (this is part of the final fight, so *SPOILERS*):

[youtube id=”Rbk9b4oIzZo” align=”center” mode=”lazyload” autoplay=”no”]

But Wait, That Action Is Not Real at All

So sometimes we see a pretty realistic fight, then in another movie we’ll see 2 guys flying across the trees, spinning and performing impossible stunts. My friends will turn and say “am I supposed to believe that is real?!” to which I reply “of course!”

Jackie Chan-style action usually focuses on realistic martial arts, meaning it is all stuff that can be physically done in real life. He typically only augments stunts and hits with wires to provide realistic or larger-than-life reactions to hits.

Others, like director Yuen Woo-Ping, often present the action in a fantasy-like world. The history can be related back to Chinese Opera and folk stories, where heroes and villains possess supernatural powers. I see it as a more stylized treatment, and not meant to be viewed realistically. I’ll talk about more specific examples in part 2.

Speed Kills

HK fans love their action fast. Most everyone will notice how incredibly fast their fight scenes are. Sometimes directors will speed up the film to even speed up the action. Newcomers might be distracted by this, but remember it’s typically there to keep the rhythm of the entire piece in sync, or to give more power to the movements. Often times action choreographers will refer to the importance of pacing, and you can often compare it to a dance routine. Some scenes might be very hard to read when you first start watching, but after you become a fan other films will look like they’re fighting in molasses.

Dubbed or Subtitled

My friends and I love classic Shaw Brothers movies and old chop-socky flicks. We also really love movies with horribly dubbed English versions where the translation is sketchy, the (voice) acting is terrible, and the pacing sounds like it was recorded in one take. Sometimes it’s really fun to watch a movie this way. However, this is obviously usually a different experience not originally intended.

Like most foreign language films, subtitled is usually the way to go for a serious and more accurate portrayal. For having fun, especially with low budget features I recommend dubbed. I’m sure I’m not the only Shaw Brothers fan who will tell you they love those movies because of/in spite of the usually terrible dubbing. I have watched the same movie both dubbed and sub’d and will attest that they are two different but enjoyable experiences.

Yes, They Know Their Lips Aren’t Synced

So you chose to go with subtitles, but you’ve noticed that the lip sync is off… way off. Even though they’re speaking in their native language! This is because most movies, especially before the 90’s, never recorded audio live when filming – they were shot silent.

The primary reason behind this was mostly two-fold. Primarily it saved them a lot of money, since they wouldn’t need any of the equipment or personnel to worry about during filming. Secondly, in China there are two dominant dialects of Chinese: Mandarin (the most common, spoken across northern China and most of the mainland) and Cantonese (spoken in the south and the native dialect of Hong Kong). It wasn’t worth the extra money to record audio during filming when they’d have to dub it for the rest of the audience anyway. They would simply record all the audio after the fact.

Another surprising factor that added to the mess was that scripts were often rough or not even finished before filming. Sometimes they would just film some placeholder dialogue which could then be changed in the recording session.

You might know dubbing is very common in most Western movies, too (it’s called ADR: additional dialog recording). We don’t notice it because they spend the time and money to make it appear seamless. Since we don’t have the same luxury with HK movies, do yourself a favor and ignore the fact that their lips aren’t synced. If you’re reading subtitles you won’t notice it anyway.

The Story Is Not Important, except When It Is

Kung Fu fans typically love wuxia for the action, and the rest is usually just filler. I typically tell people not to expect much with story, especially with movies of Jackie Chan, even though he’s in my pantheon of favorite directors. Often this is the case, but sometimes the story really pushes the film beyond the usual constraints. Movies like Ip Man, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, or 36 Chambers of Shaolin not only showcase top-notch kung fu, but wrap it up in a compelling and/or fun story. Don’t expect a great story every time (or most of the time really), but conversely don’t accidentally ignore a good story in the process.

Kung Fu Is Not Just One Flavor

I think a lot of people who don’t know the genre assume every kung fu movie is the same thing over and over again: guy bumps into another guy, insults are slung and fights ensue for 90 minutes. But like most genres, kung fu is celebrated by many different interpretations and sub-genres. Some prefer fantastical, some prefer realistic. Some incorporate acrobatics, some do realistic street fighting. Others love gratuitous violence, others mix it with comedy. If you watch enough you’ll probably discover you like certain kinds more than others, but it’s the variety that always helps keep it fresh.

Cheng Cheh’s movies were always a violent bloodbath. Jackie Chan is synonymous with action comedy and are almost always family-friendly. Lau Kar Leung showcased and celebrated very traditional and authentic kung fu. Bruce Lee showcased his Jeet Kun Do, which make his fight scenes resemble more Western-style action with big single-hit takedowns. Yuen Woo-Ping was a master of “wire-fu” featuring high-flying fantastical action. Stephen Chow mixed kung fu with Looney Tunes-style antics to hilarious results.

These genres also helped spawn sub-genres. Sammo Hung popularized the Jiangshi genre, or “Hopping Vampire” flicks, which were blends of horror, action and comedy. John Woo famously popularized “gun fu,” which took the cinematic style of kung fu movies and applied them to gunplay. So just because you’ve seen one does not mean you’ve seen them all.

Continue to Part 2

For the newcomer, I hope these notes will help keep your first films in perspective as well as help you appreciate your viewing experience. Continue to Part 2 right here.